It takes a lot to get me worked up, but here we are.

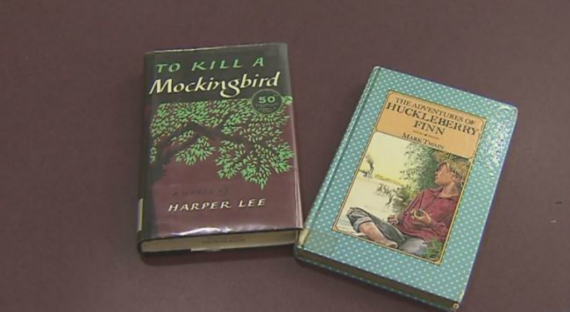

Last week, news reports out of Duluth, Minnesota, noted that students in Duluth will no longer be required to read Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird or Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a part of their high school English curriculum. Every so often, stories like this pop up, with some district somewhere deciding that students no longer need to read the “classics” when there are less challenging options available.

In this case, Michael Cary, the director of curriculum and instruction for the district says, “The feedback that we’ve received is that it makes many students feel uncomfortable. Conversations about race are an important topic, and we want to make sure we address those conversations in a way that works well for all of our students.”

On this, I call bullshit, and I will die on this hill if I must.

When and where did our society adopt this idea that being uncomfortable is a bad thing? At some point, we decided that we must only exist in an echo chamber with people that a) agree with us or b) don’t push us to think about things in a way that conflict with our own previously held beliefs.

The problem is that being uncomfortable inherently allows for personal and emotional growth. Being comfortable allows for stagnation of the mind and body. That’s the real problem. Great, important art (like these books) should make you uncomfortable. That’s how they enact change.

Instead of embracing the discomfort that these texts provide (and they are uncomfortable in spots), this school district has decided that other texts with similar messages will do just fine. You know, texts without “oppressive language” because, as Stephan Witherspoon, president of the Duluth chapter of the NAACP, says, “Racism still exists in a very big way.”

Yes, racism does still exist. There are no arguments from me on that point. However (and here’s the rub), these books aren’t racist. Never have been.

The irony is thick because here’s what the Duluth school system is essentially saying: Racism is a problem, and we are going to combat that by removing two of the most anti-racist, inclusive books in the canon of classic American literature from the curriculum.

It’s lunacy.

In the interest of full disclosure, I was an English major in college. Then, I taught high school English for five years before going on to get my Master’s in English Education. So I’m more than familiar with this issue. In fact, in every single one of those five years of teaching high school English, I taught both of these books. So, yeah, I have a rooting interest here, but it’s also an informed one.

In an effort to streamline the conversation about the appropriateness of these texts, I want to focus on The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It is, far and away, the more problematic of the two texts now banned by the Duluth schools. The problems for most when discussing Huck Finn’s appropriateness, I would guess, are two-fold. First up is the over 200 uses of the word “nigger” in the book. And you bet your ass that’s problematic.

There’s been hundreds of journal articles written about how best to address this inflammatory, loaded word in a classroom of teenagers. I don’t know if there’s a right answer here, but there is a “best practice” consensus among English teachers. Nancy Methelis, a high school English teacher and often-cited Huck Finn teaching expert, explains here:

I generally tell my students at the beginning that this word is not going to be used in class because it could hurt people in the class. I know that there are educators who feel that the word must be confronted, must be said, and must be discussed, and I’m not saying that this isn’t the correct intellectual approach to take. But as a teacher in a public school with young students, high school students, I think that the possibility of hurting some students and desensitizing others is too high a price to pay. . . . Names do hurt people every day. There has to be a place where students feel safe, and schools often provide those places. I’m determined to provide that type of atmosphere. Then students can talk.

With the right approach, students can still feel “safe” and have meaningful, incisive discourse about a difficult topic. If it’s handled well of course. So, if you’re not going to use the word, what does the teacher, do?

Methelis is not, however, suggesting a modified text. Nor am I. Students should read the text as it was written. If reading aloud (as I often did), using a euphemism (“n-bomb” is a personal favorite) allows the eyes to read the word while the ears are not dealing with the verbal equivalent of a stick of dynamite.

[media-credit id=5 align=”aligncenter” width=”480″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

To be clear, I strongly oppose the use of modified texts that use kid gloves, replacing or censoring away words that may cause discomfort. If you do that, however minimally, you’re not teaching the same book anymore. It becomes a translation of sorts. As scholar George Steiner says of the act of translation, “the ‘miracle’ is never complete.” Each permutation “falls short” of the original. When students get done reading Huck Finn or To Kill a Mockingbird, they should be able to say that they’ve read the actual text as it was intended when it was published. Not some chopped up Frankenstein’s monster of supposedly oppression-free language that would rightly infuriate Mark Twain and Harper Lee.

The second issue most have is tied to the first. That, because of its excessive use of the n-word, the text itself espouses racist ideals.

In no uncertain terms, Huck Finn is a book about race, but it is far from racist. Mark Twain presents the society surrounding Huck as being little more than a collection of corrupt rules and principles that lack rationale. It is a world largely populated by people that seem to be well-meaning but are instead marked by cowardice, fear, and ethnocentricity.

Twain himself married into an abolitionist family. He wrote an 1869 anti-lynching editorial. He paid expenses for black students at Yale Law School in 1885. He advocated for reparations. All of this information can and should be used to establish context in the teaching of Huck Finn.

As a conduit for the racist society that Twain found himself in yet abhorred, Twain used Huck himself. The story is told through Huck or, in passages where other characters speak, experienced through him. Students should be taught to embrace Huck as being ignorant, innocent, and uncivilized. Because he is 14 years old and uncivilized, his positions and beliefs come largely from the conventions of society. His saving grace, however, is his willingness to question these conventions.

Huck’s foil, so to speak, is Jim, the runaway slave. He is the breathing contradiction to what Huck has taken as fact. Jim is human. He is capable of great love and empathy and intelligence. Through the course of the novel, Jim asserts himself as much more than just a slave. Huck sees Jim establishes himself as an independent, thinking, feeling adult. A truly free man. Much more free, in many ways, than Huck.

I often hear people espouse the ideals of a system of education that teaches students to think for themselves, to engage in critical thought while, at the same time, detecting the ever-prevalent bullshit that society now, much like in Huck’s time, heaps upon us daily.

How, though, can high school students learn the same willingness to question conventions if they’re fed sanitized versions of texts or, worse, comfortable texts, by the very institutions that are supposed to exercise this critical thinking muscle?

Huck Finn is so much more than a story of a child and a slave floating down a river. It’s more than an adventure tale. It’s more than its racial epithets. It’s one of the truest depictions of how important it is to be pushed out of our comfort zone and embrace things and people that are different from us, just as Huck does to Jim.

Huck Finn has been banned before and it will be banned again. As far back as 1885, the Concord Public Library deemd it “absolutely immoral in its tone.” The book and its message, however, has held on, as true classics tend to do.

Here’s what I know, though. As a former teacher and having known hundreds of educators, I don’t know of a single one that would ever advocate for the banning or censorship of a book. And certainly not this one.

Regardless of what the fools up in Duluth end up doing, I beg other schools considering similar action: Please make your students uncomfortable. Please make them read and learn things that challenge them. Please don’t believe that because you don’t make them read this, you are doing them a favor and shielding them from life. You’re not. There is no way to shield them from challenges. The best thing you can do is equip them to deal with them. Those challenges will likely be a lot bigger than being made uncomfortable by words on a page.

Most of all, don’t f*ck with Huck.

[media-credit id=5 align=”aligncenter” width=”555″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]